So glad I retired when I did. Packed in the drafting table. Started using the T-Square only to cut drywall. Donated my triangles to the carpentry shed. Rolled up the vinyl.

That is because in forty years of practice I spent the last twenty worrying about whether or not the receivables would be sufficient to cover payroll. Lying in bed, worried for the families that depended on my (our) success to put bread on the table. It was always draining. My exhaustion sometimes overwhelming. I did not tire of design. I did not tire of contractors. I did not even (completely) tire of clients (even though most wanted a Cadillac while offering a budget insufficient to acquire a Lada). These were met as daily challenges. Why, even the unbridled arrogance of our Department of Works and Transportation only gave me cause to chuckle.

No. It was always the money to pay those who worked for me. And to continually inspire them.

So I cannot begin to imagine the agony of trying to hold an architectural firm together right now, and I am so fortunate, so very fortunate, that I don’t have to.

The internet and social media (something that I have lapsed into during self-isolation) are full ideas as to an alternative approach to design if and when we ever come out of the other end of this thing, i.e. the new normal. Perhaps, just as it may be clear from economic and healthcare disciplines, architects have been going down many errant and/or misguided paths.

I designed a great many office spaces in my time. These used to be planning minefields because just about everybody got four walls. The assigned square foot area (handed down from “head office”) would be meticulously measured by every manager and employee. Who got windows and who did not was tantamount to a turkey with ten legs. Once, when struggling with how big each office should be for a project space for oil executives, I became frustrated with the various areas required by each manager (and their company directives). My boss at the time made the following suggestion:

“Take each of their salaries and divide by 100. That’s how much space they get.”

I thought he was joking. He wasn’t.

In the waning days of my career there was a momentous shift toward landscape office (open plan) and hoteling (where you generally work elsewhere, so to get a space in the office you reserve some ubiquitous workstation in advance for a specific duration).

So … a couple of things wrong with this. Firstly, open plan office schemes are typically done on a shoestring budget (to save money). These cheap knock-offs don’t work, especially acoustically. You need to spend an equivalent amount of money as you would have had you been designing enclosed offices. And secondly, people are now finding, en masse, that working from home may not be optimal, for some, more so than others. So corporate managers: don’t assume it works for everybody. It doesn’t. And there’s a relative scale.

When people came to work sick, we used to say to them, “If you won’t go home, just stay in your office.” So think about that for a moment. And combine that idea with stainless steel door hardware that can retain a virus 25 times longer than copper alloys…

We also did a great deal of retail sector work at our firm. In the old days, you went into a shop and had the clerk fill your order from behind a counter. Behind the counter was off limits. Everybody knew that. It was social distancing at its best. Nowadays, retail design is set up more and more so that you do everything yourself – which saves retail giants a pile of money. So now you can be assured that the shopper that went before you has likely infected every aspect of the self-serve checkout imaginable. That’s what is awaiting you and every shopper behind you, perhaps for days. Someone recently suggested that “you may get more than you bargained for”.

How soon will we forget the “front line workers” that kept the food industry chain going during the pandemic? How soon will the plexi-glass screens be coming down? Or are these new design elements?

There are a great many cities that now (as I write) are looking to close off thoroughfares to vehicular traffic to allow people a greater opportunity for social distancing, which is now impossible or difficult on many of our sidewalks. The “stay inside” promotion is only going to work for so long. In order to maintain physical and mental health, we need to get out. When we do, we may find social distancing difficult. I expect that there will eventually be a Covid-19 death attributable to someone being run over on the road while trying to avoid coming within two metres of someone else. This speaks volumes about how we may need to rethink our car-centric lives to put pedestrians and cyclists first.

For St. John’s this represents an opportunity to actually keep snow on the streets rather than plow in the entire depth of a five foot sidewalk.

Architects are all about design for people. If they weren’t, the everyday person would only ever be subjected to design for profit. We are one of the few professions where there is an unseen responsibility towards the common good. The profitability of many restaurants and entertainment venues relies on seeing how many people you can pack into a given area. So much so that codes exist to limit overzealous owners who tend to see clients as sardines. Under the guise of providing intimate space, all manner of seating arrangement, screens, and indoor plantings have been devised by designers to separate people who really are practically on top of one another. People who often don’t have enough sense to stay home when they’re sick. We may have to go back and have another look at this.

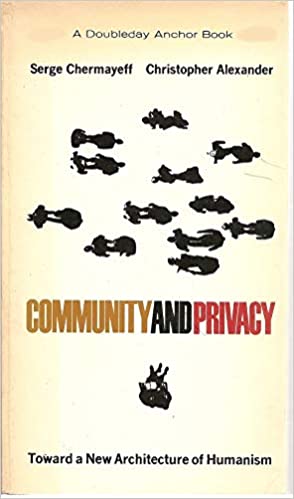

Serge Chermayeff and Chris Alexander wrote a seminal book in 1965 entitled “Community and Privacy”. You can be forgiven for having never heard of it. But for students of architecture, it was like Gray’s Anatomy – essential reading for turning young architects into socialists (which is a good thing for the public). In this book, all constructed space was neatly categorized and defined: private, semi-private, semi-public and public. And it offered up all the ways in which the intent of each type of space could be both consciously and sub-consciously reinforced so that we could all cohabitate and negotiate our world peacefully and securely. But we have been living in an era when profit routinely trumps people.

Housing is the best manner in which to test Chermayeff and Alexanders’ thesis. When these four types of spaces are clearly definable, neighbours can live in close contact but with clear boundaries. This not only makes everyone happier but, critically at this time, healthier. The postman, the Skip-the-Dishes gal, the courier, the public health nurse – everybody – are cued as to the boundaries. The principles, I would argue, are intrinsic to multiple housing and low-income housing. Unfortunately what we get is typically low budget housing. Social distancing be damned. Who is going to pay for those walks, overhangs, porches, galleries, and flower beds anyway?

In a somewhat opposing vein, another tenet of architectural theory lies with communication and cooperation. This is the way in which designers conceptualize aspects of the built environment to facilitate human interaction. The idealization has been creeping along to the point now where banks don’t look like banks anymore, they look like coffee shops. Physical items meant to communicate (bulletin boards, signage, wayfinding) architects nefariously placed where the most people could avail of their instructional nature (communicate) and in doing so, take advantage of the human tendency to socialize and offer assistance (cooperate) by sharing knowledge. We may need an app for that now.

The famous Dutch architect, Herman Hertzberger, had this idea of “instigators”. These were physical aspects of his designs that were undefined, but offered up spur-of-the-moment uses that we left to the creativity of the user. A shelf fixed outside the door of a seniors apartment offers a myriad of potential: a spot to place a bag of groceries or handbag while one fishes around for keys, an easel to display art or handicrafts, a gallery for pictures of grandchildren, a plinth on which to place a seasonal bouquet. Just imagine. What a marvelous spot to place a hands free take-out order or that parcel from Amazon. We have grown into such a miserly design mindset that everything demands a function.

I once (almost thirty years ago) proposed to oil company engineers that the production platform living quarters should really have some multi-purpose rooms. They looked at me as if I had proposed a bouncy castle. I responded: “It’s where women can meet to discuss issues pertinent to their life offshore. It’s where like minds can pursue hobbies. It’s where Muslims can go to pray. It’s where you can convene an impromptu or emergency meeting.” They pretty much assured me that none of that was going to happen on their watch. But I prevailed and eventually won the argument.

In the post-pandemic design world, good design would look after and respect everyone. A new design paradigm that recognizes how we are all vulnerable might make (for instance) accessible design or transgender design redundant. Inclusivity and diversity should be the starting point of the new age.

This is only to say that we cannot predict the future, let alone the future of design, but it certainly wouldn’t hurt if, in our built environment, we put people out in front of profit and rewarded everyone who did.

This may be pie in the sky. Perhaps I should just stick to worrying about how my former colleagues are going to navigate this thing.